Marco Cadioli – Necessary Lines

Link Point, Brescia, January 18th, 2014

Marco Cadioli is a photographer and, like all photographers with an important project, he travels the world looking for his subjects to immortalize them and present his particular point of view. However, instead of wondering the infinitely detailed and always changing “sublunary world” we walks the incorruptible digitized image of the globe recorded by satellites, which Google makes available online.

Cadioli, Net Art teacher at the Academy of Fine Arts in Brescia, is not new to this kind of photographic research documenting the network, having worked under the pseudonym of Mark Manray 2005-2008 as a photo-reporter in Second Life, documenting a reality that, as he himself says, “When will disappear will not even leave the ruins.”

The exhibition “Necessary Lines”, which opened on January 18th, 2014 at “Link Point” in Brescia, starts with black and white images where the photographic prints, applied to the wall without a frame, report polygonal lines that immediately exhibit a strong regularity, with parallel trends and sharp edges or right angles.

We do not know the scale of these images and the imagination could bring us back to known configurations, such as the milling path of a machine or an RFID antenna, in any case we think of something man-made.

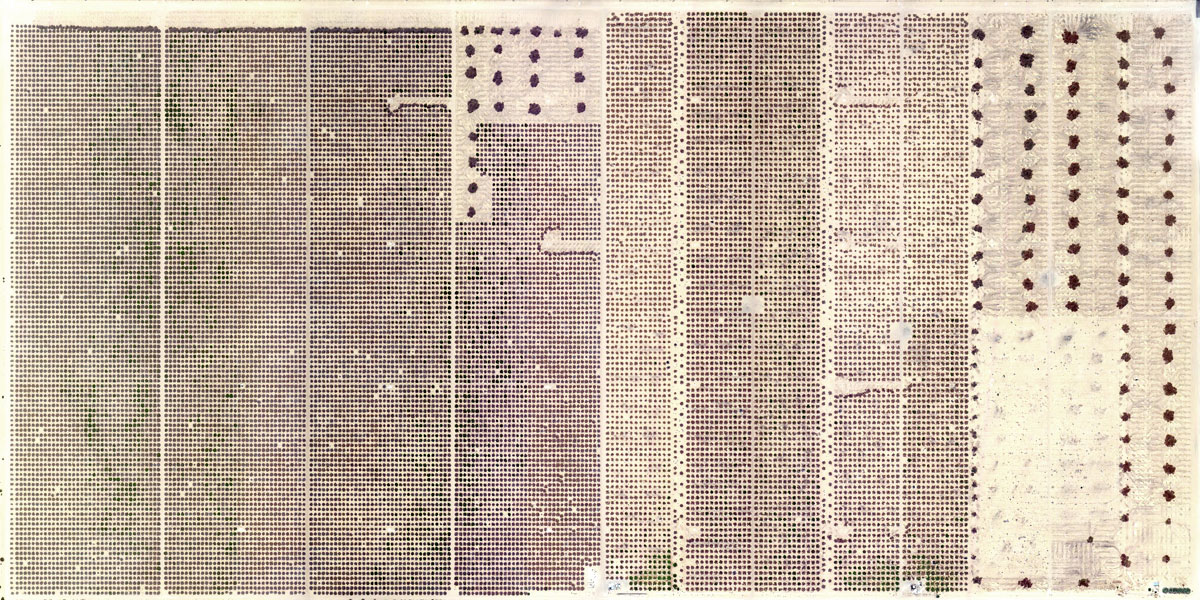

Looking with more attention at the photos and getting closer, we begin to discover irregularities in the graphs and extraneous elements to the overall design. We understand that Cadioli has deliberately left visible at the edges of the lines what correspond to the roads, and from this we can guess that the blacks dots at the edge are poles, maybe of the power line, or more nostalgically, the telegraph. You then start seeing the houses and silos, and there is no doubt that these traces in the land are cultifavtion fields. The order of magnitude of these fields is a mile or half a mile, quite large for European agricultural conception, but not for the U.S. highly automated approach to agriculture. These lines were probably made with machines controlled by a GPS, then through other satellites.

The exhibition continues with another set of colour images, where the ochre land is the background to another type of regular figures; in these images the fields, from far away, look like the columns of a newspaper, and in fact one of the works is titled “Page One”.

If it’s the regularity on large-scale that surprise at first sight, the focus shifts quickly to the irregularity: one of the paths of the machine has taken a chaotic course, a tiny cyan rectangle contrasts with the yellow background and shows a swimming pool. Now we move on a human scale and begin to imagine stories about men who live in this place. The large geometric lines of the field, had the effect of a calling signal launched into space, and we landed right on the edge of the pool, an oasis in the desert of Arizona, and we would like to go back there at least virtually, to zoom in, trying to figure out if we can meet someone bathing. But Google has updated the maps and there are no longer those lines, and since now vegetation is grown in the field, we do not find more of the same place. The photo of Cadioli freezed the unrepeatable moment of space-time.

But maybe, if we have not found the man who inhabits these places, we have found the Man who inhabits earth and tries to give it a shape that is regularly represented with Cartesian axes, with “necessary lines”, to be logically understood.

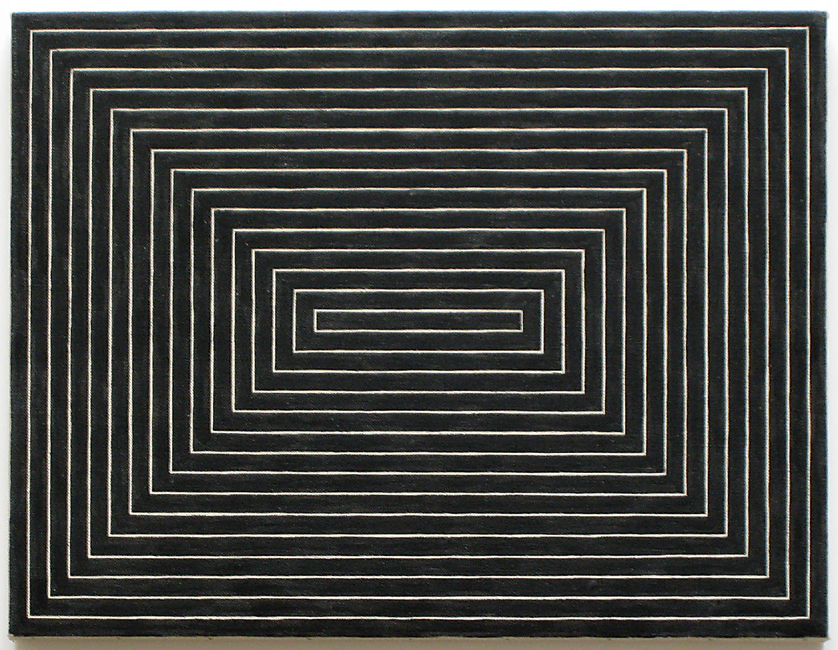

Also the “Necessary lines” of the black paintings of Frank Stella, as defined by Carl Andre, can be read under this key: the minimalist artist, eliminating the superfluous, finds a regular geometric line that deeply characterizes man. Regular up to a certain extent because, the hand-painted, the lines of Stella maintain that characteristic of slight variability that makes them attractive; from a distance you see the ideal line, coming close you can see the human, phisicaly irregular, brushstrokes.

Cadioli found himself in front of unintentional works of land art. Physically printing them and presenting them in a show, makes them really artwork and subject of discussion because, in fact, the art always goes behond “What you see is what you see.”